Agenda-setting intelligence, analysis and advice for the global fashion community.

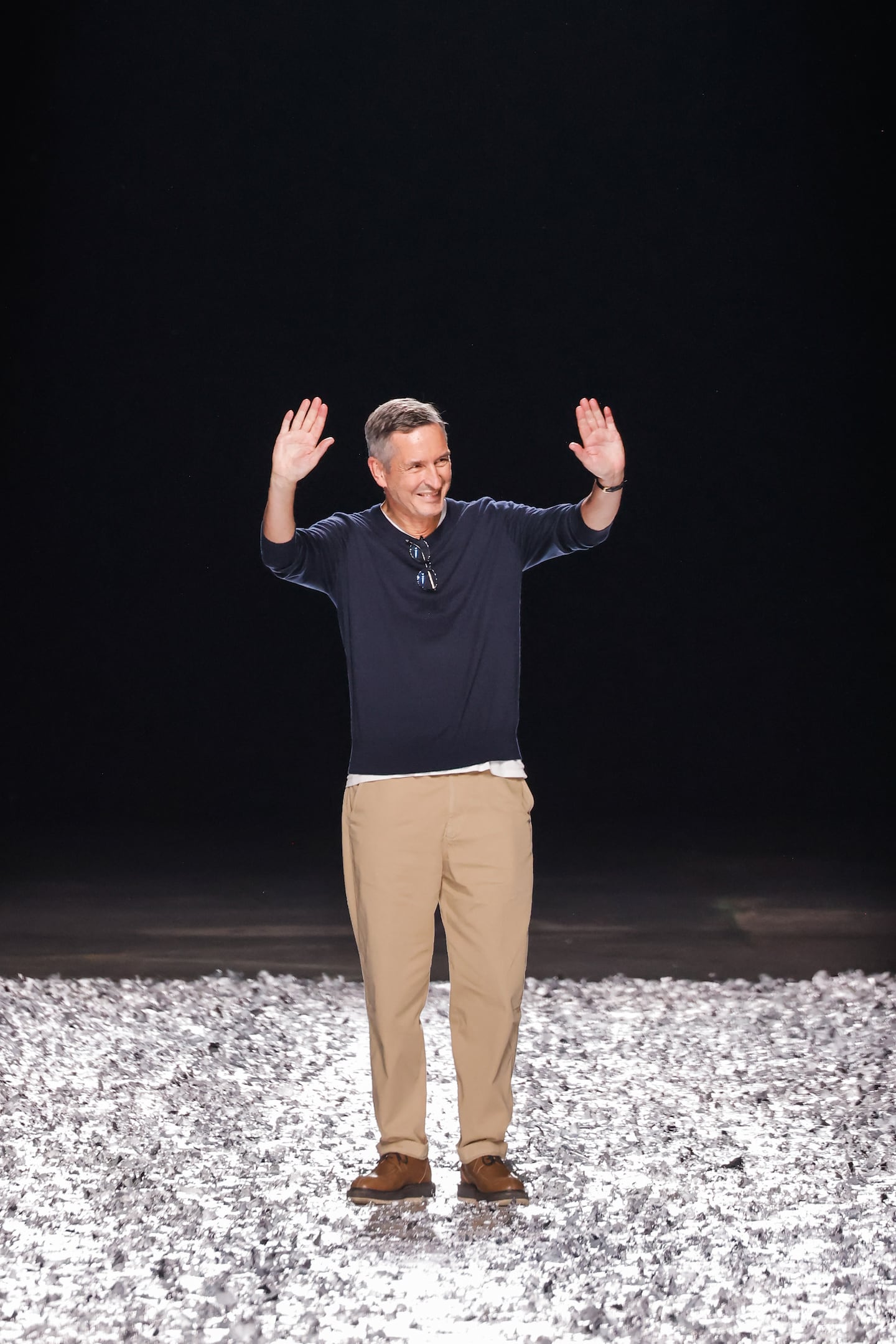

PARIS — On Saturday night, Dries Van Noten waved goodbye after a 38-year career in which he changed fashion: not just the way people wear clothes, but the way they experience them, too, in shows that defined the idea of intelligent spectacle. His last was no exception to that rule. It was the perfect conceptual bookend, in that it was a men’s show and his first actual show was a menswear presentation for Spring 1992. Now, brace for full disclosure: I’ve worn Van Noten’s clothes more than any other designer’s. (For his farewell, I shoe-horned myself into one of his sequin-covered shirts and spritzed myself with his Cannabis Patchouli scent). I was also at his second show in 1992, and just about every subsequent presentation, and most of them are benchmarks of my catwalk-adjacent career. So many memories, so much emotion. So don’t expect too much objectivity.

When Dries and I had a sign-off chat about the 38 years, the 150 collections, the 129 shows, I loved learning that there was also a practical consideration in the timing of his exit. Isn’t it better to start your next chapter as summer beckons? If he’d sayonara-ed during the women’s shows, he would have been gazing into the cheerless maw of winter, when long dark nights might inspire doubts about his decision to quit, even though that decision was actually made a long time ago.

Once Van Noten and his partner Patrick Vangheluwe decided they had a lot of living still left to do, they began the search for someone who could take over. At first, they wondered if there would even be enough substance in the business to make such an idea worthwhile. In 2018, Spanish fashion and fragrance company Puig took a majority stake. “After the valuation, when we looked at what we stood for, we realised that other people could also do their own interpretation of it,” said Van Noten. Maybe that was all the permission he needed to step aside. “Now it’s up to other people to use the principles that we’re standing for. Colour, prints, embroidery skills, the craft, the menswear fabrics … there are enough people who can work on those things and let them grow into something else.”

I told him I just couldn’t imagine Dries without Dries. “No!” he countered instantly. “The last thing that I want is that they do Dries without Dries. I would be sad that the next collection didn’t have one piece of colour, not one piece of print and not one piece of embroidery. Then I say wrong. But as long as they do a new interpretation of that with a new eye in a different way, then why not?”

ADVERTISEMENT

The concern with such a particular aesthetic is that, when someone else attempts it, it becomes pastiche. “No, I absolutely don’t want them to do it the way that I do,” Van Noten reiterated. “I always say where you have to be the most creative is choosing the right people around you. And I always chose people who are quite different and have quite different tastes to my taste, to challenge me, to make the combination of my vision and their vision something exciting. Really the last thing I want when I see somebody who applies for a job in our team is that they present a file which looks very much like what I’m doing. I always say, this I can do better than you, so you do what you can do well. I think it’s going to be a change. And I think maybe there’ll be certain moments when I say ‘Oops, this I didn’t really see coming.’ But as long as it makes sense when the label “Dries Van Noten” is in a garment and you don’t say, ‘Oh my goodness, what did they do now with the house?’”

It’s an obvious assumption that a last collection would be a look back. Van Noten didn’t want that. Instead, he delivered a blueprint that offered a network of ways forward. “Maybe it’s going to surprise a few people that it’s not more nostalgic. But I’m happy with it. I still wanted to put a few steps forward so I worked really hard, to use new materials, try different things, maybe with success, maybe with some errors, just let’s try something. It wasn’t easy, because of course you want to tell a lot. Maybe too much. I was a little bit split. Shall I do that? Do I care? It’s my last one.”

There must have been some editing in the days after we spoke because the collection Van Noten showed had a distinctive coherence. Nothing “too much.” It was largely sombre — perhaps the significance of the occasion was inescapable there — but it had a rich seam of the muted opulence that’s been a longtime Dries signature: dully gleaming lamés, old gold bullion, foil coatings that loaned a liquid languor to jackets, trousers and the baggy shorts that have become a menswear staple. In fact, languor was the dominant mood in the general loucheness of floor-sweeping coats, pants puddling on the ground and jackets sliding off shoulders, and almost everything, no matter how dressed up, paired with sandals. Hannelore Knuts in an oversized white double-breasted blazer was the essence of Van Noten’s man-styled womenswear, closely followed by Kirsten Owens in a black officer’s coat limned by bullion embroidery. But more than anything else, it was Van Noten’s delight in high/low contrasts that sealed the look that will be his legacy: gold lamé jacket and cotton drill pants, imperial purple panné tank and baggy grey linen pants, gilding and matt black, devoré and the diaphanous, the marriage of tradition (an ancient Japanese printing technique called suminagashi) and technology (a crinkly plasticky polyamid).

For now, the idea of legacy is something he finds a little confusing. “I think you’d have to judge what’s left of it in five years.” But he suggested that where and how the clothes were designed had a part to play. Antwerp has been fundamental to his success. “When we started it was like one big adventure.” Van Noten was laughing when he remembered the early days of the Antwerp Six. “We were from Belgium, not the most fashionable country, and, at a certain moment, we thought to change our names. We were very jealous of Marina Yee and Martin Margiela because they had international names. But Walter Van Beirendonck and Ann Demeulemeester and Dirk Bikkembergs and Dries Van Noten were not easy-sounding names. I still remember the discussion that we had and the answer was, ‘Yes, but if you can say Yohji Yamamoto, you can say Ann Demeulemeester.’ So we didn’t do it.”

Memories aside, he admitted his departure had occasioned the odd tear, though he was emphatic in his declaration that he wasn’t any kind of nostalgist. The first time the collection was hung in the studio in the order in which it was to be shown, he came in to work early. “Here I was at seven o’clock in the morning and I looked at it and I said, ‘Oh my goodness, this is the last time that I will see this, that is really my child hanging there.’ And that was really difficult.” Van Noten said he cried. And he wasn’t embarrassed to say that wasn’t the first time. Or the last.

Mostly though, when he went back to old collections, he was struck by how much sense they still made. “Clothes don’t have to have a short life.” That has always been one of Van Noten’s guiding principles. “When I started in the 70s, the idea of fashion was that it was all fast forward evolution. ‘It’s so last season,’ ideas like that. That for me is not true. I succeeded in creating clothes which look fashionable without going out of fashion in one way or another.”

He has a remarkable aide-memoire in that respect: the two-volume set published in 2017 as a celebration of his first 100 shows. (Disclosure: Susannah Frankel and I wrote the text, and I’m as proud of the finished product as anything I’ve ever done — I warned you I’d shucked objectivity). Van Noten said it made him happy when he looked at the books and the images were still so resonant. “You can feel the atmosphere of the show,” he said. “I’m a storyteller and for me, the 0-100 book is not like a fashion book, it’s a storybook. And that’s something of which I’m really proud. What surprises me in my own work is that there is a clear continuity, but there’s also enough change so it’s not like I repeated myself. We have a saying in the company, when you see the trick you lose the magic. I didn’t really use the same trick too many times. I think there was still a clear evolution.”

Speaking of aides-memoires, Saturday night’s presentation was as studded with them as it was stuffed with fashion heavyweights turning out to bid Dries farewell. Karen Elson wore a pea coat adapted from the epochal Winter 2011 men’s show which saluted David Bowie’s incarnation as the Thin White Duke. There were traces of python which tracked back to the Bryan Ferry-inspired glam rockery of Winter 2006 (a show which took place in the École des Beaux Arts under multi-coloured umbrellas upended and unfurled to create a ceiling. Surrealists everywhere cheered). Van Noten’s hibiscus and palm tree prints were old friends. They’ve lurked in my closet for years. But the greatest aide-memoire of all was the marchpast of familiar faces, opening with Alain Gossuin, who walked in Van Noten’s first show. Daiane Conterato was always one of his favourites. So were Debra Shaw, Will Chalker, Clement Chabernaud and Hannelore. Kirsten Owen had travelled from her home in Vermont for the evening. She had always felt such love from Dries and Patrick when she worked with them in the past, she felt it was the least she could do to show some back. There were newer favourites too: Leon Dame, Jonas Gloer, Malick Bodian. Van Noten’s fashion family covered a generous expanse of generations.

ADVERTISEMENT

From my experience, designers exist in a state of permanently agitated dissatisfaction. Ask them about the collection they just showed today, and they’ll say they’re already thinking about the one they have to start tomorrow. I asked Dries if there was ever a moment when he got home the night of a show and was able to tell himself that it couldn’t have been any better than it was. “For me, the closest to perfection was the 50th show, on the table.”

For that presentation, Spring 2005, the venue was a warehouse on the outskirts of Paris. 500 guests were served dinner at a single long table bisecting the shadowy, cavernous space illuminated by 130 chandeliers which, when service was over, rose to accommodate the transformation of table to runway. The production highlighted the invaluable contribution producer Etienne Russo has made to Van Noten’s career. He worked on all 129 shows, often achieving breathtaking effects with nothing more than light, shadow, scale and knife-edge ingenuity. In 2005, for example, there was no sophisticated software to coordinate the descent and ascent of the chandeliers nor the commemorative book that each guest received at their place settings. “The lighting guy was saying that to bring the chandeliers and the books up and down at the same time, a whole group of switches had to be moved simultaneously,” Van Noten recalled. “So they took a long piece of wood and two people pushed the switches all at once.” From such a human, pre-digital touch was jaw-dropping magic made. “The only thing that went wrong is that one model walked a little too slow in the finale. The waiters were students but they did it perfectly, not one dish fell on the ground, no one bumped into each other.”

Van Noten used the same location for Saturday night’s show. I did wonder whether he might be about to revisit past glories, but he is not sentimental like that. He claimed the choice was out of necessity because everything else was booked for the Olympics. So, no table, though Russo once again bisected the space, this time with a long sliver of catwalk carpeted with drifting leaves of silver foil that the models kicked through as they walked. I thought back to Spring 2014, same effect with a backdrop of fluttering gold leaf. (The opulence! The simplicity!)

Back in 1976, when Van Noten announced to his parents that he would rather train to be a designer than work in the family business, his father wasn’t happy. “Not with my money,” he declared. So Dries had to work to pay for his fashion studies at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Antwerp. But twenty years later, when Van Noten père first came to visit Rigenhof, the magical 50-acre estate that Dries and Patrick have created outside Lier, he was impressed enough to concede that his wayward son had made the right decision. In 2017, Van Noten was made a baron by the King of Belgium. A month ago, he became a Commandeur des Arts et des Lettres in France. They’re honorifics which suggest a passage into an august old age. It’s not a prospect which troubles him. He insists he’s never been bothered by ageing, aside from a hiccup at 36. “That was the biggest shock, you’re not young anymore and you see friends from school with kids on a bicycle.”

But by his own account, Dries and Patrick have excelled at being gay uncles, although his brother’s grandchildren, aged six and eight, recently had to wrap their heads around the confusing realisation that the guys they thought were their parents’ age were actually the same age as their grandfather. “They thought of their grandparents as old people but they didn’t think of ‘Dries and Patrick’ as old people. I was so proud.” Van Noten laughs at the irony. Still, it reinforces how important it has always been for him to be surrounded by young people. “Sometimes I feel a bit that I’m a vampire. I need them to feed me. They have to challenge me, they have to push me forward. And that was something I discussed for a long time with Patrick. How can we fill that in? We’re not even middle-aged anymore. So with the projects that I’m working on, I’m still involved with young people because that keeps me young. If I thought it was only going to be me and Patrick and a few friends the same age as us? Come on, no, don’t do that to me!”

So they’ll travel. Now they will no longer be juggling Italian and Belgian production schedules in the summer months, Dries and Patrick might get a proper break. “Don’t get me wrong, the last thing I want to do now is take three weeks of holiday. I think I’ve learned that you can also have a good life without that. We dream now to fly to whatever city in Italy, get a car and drive to our house on the Amalfi coast, take our time to go from one place to another, stop at a nice restaurant for lunch. Though of course I would love for us to travel a little bit further, to see more things. I want to go back to India. It’s a while ago and my soul is definitely still a little bit in India. I want to go to Scotland. I’ve never managed to get there. And I would love to go to New Zealand.”

Everything was still very present-tense for Van Noten when we talked. As in, “My life is fashion, and fashion is my life, when I look at something, it’s always a function of creating fashion.” No surprise really, but I wondered what happens when fashion is no longer present as a creative outlet. “Honestly, I’m afraid of that,” he answered. He worried about “the black hole” one could fall into once you’ve closed the door. “I don’t know how frustrated I’m going to be that I can’t do that anymore, to translate creativity. I’m still going to be involved in the company, I’ll still continue to work on beauty and the perfumes because it’s a project which I really like. I’m still going to be involved with store designs, luckily enough. If I see a good artist or a nice piece of furniture, I can still take a picture on my phone and send ideas to the architect. This hopefully can continue.” He laughed, a little nervously I thought.

But there was one final perfect element on Saturday night which consolidated Van Noten’s enduring grip on fashion’s imagination — mine at least — and that was the soundtrack. I can’t think of a favourite Dries show without the music that accompanied it. To select a mere two from an abundance of riches: the tick-tock dissection of Bowie’s “Golden Years” that accompanied that Thin White Duke tribute in Winter 2011 (“Heroes” received similar treatment for the women’s show that followed) and the exultant cacophony of Godspeed You! Black Emperor’s “Motherfucker=Redeemer” that soundtracked the hundreds of thousands of fairy lights rising and falling in curtains for the climax of the Winter 2003 women’s show. They will resound in my head till the day I shuffle off this mortal coil. The Dewaele brothers David and Stephen, working as either 2manydjs or Soulwax, have been responsible for many of the aural counterparts to Van Noten’s artistry. So it was appropriate they provided the soundtrack for his send-off, and even more so that it involved a complicated tapestry of Bowie music, culminating in “Sound&Vision,” two words that define everything a Dries show was about.

ADVERTISEMENT

I asked him if there was one soundtrack that was a personal favourite. “Yes, absolutely. Malcolm McLaren, the punk collection [Winter 2010, for the record], the first one we did at the Hôtel de Ville, where he mixed the music from ‘Vertigo’ with the sounds of punk and cowbells and things like that. I had to phone him to explain what the collection was about, and he said, ‘You’re also using some punk elements?’ and I said, ‘It’s not really punk, it’s the idea behind punk.’ And he said, ‘Ok, now I want you to describe the collection, but don’t talk to me, I’m giving you two minutes and you have to shout to me what the collection is about.’ So I was on the phone screaming to him, and he said, ‘Now I get it. That’s what I wanted to hear.’ That was the only contact that I had with him, and afterwards he came back with that incredible masterpiece of a soundtrack. And it was his last masterpiece. He couldn’t be present at the show, because he knew it was his last days. I think he passed away five days later.”

McLaren called the piece of music he made for Dries “Requiem to Myself.” Requiems usually accompany a mournful send-off for the dear departed, and it was typical of Malcolm to take it upon himself to compose his own. But even though Saturday night was a swansong and tears were shed, there was nothing mournful about it. Dries made it a quarter of the way down the catwalk, gave his usual diffident wave and turned back as a massive mirrorball was revealed in all its slowly rotating glory. “I Feel Love” rang out on the soundtrack. Was he walking into a disco sunset or was this a new dawn? I hope he felt the love, like I hope I wasn’t alone in my faith that we have still to see Dries Van Noten’s last masterpiece. After all, he assured me this wouldn’t be our last interview.