Agenda-setting intelligence, analysis and advice for the global fashion community.

Agenda-setting intelligence, analysis and advice for the global fashion community.

Opens in new window

Opens in new windowFar from resolving in 2024, the fashion industry’s supply-chain volatility of the past few years is set to continue. Upstream apparel suppliers and manufacturers have undergone significant disruption, where changes in consumer demand have resulted recently in a sharp decline in factory utilisation, widespread layoffs, and delayed investments. As brands and retailers look to scale up capacity to meet renewed demand, they may start to feel the repercussions of recent upstream strains.

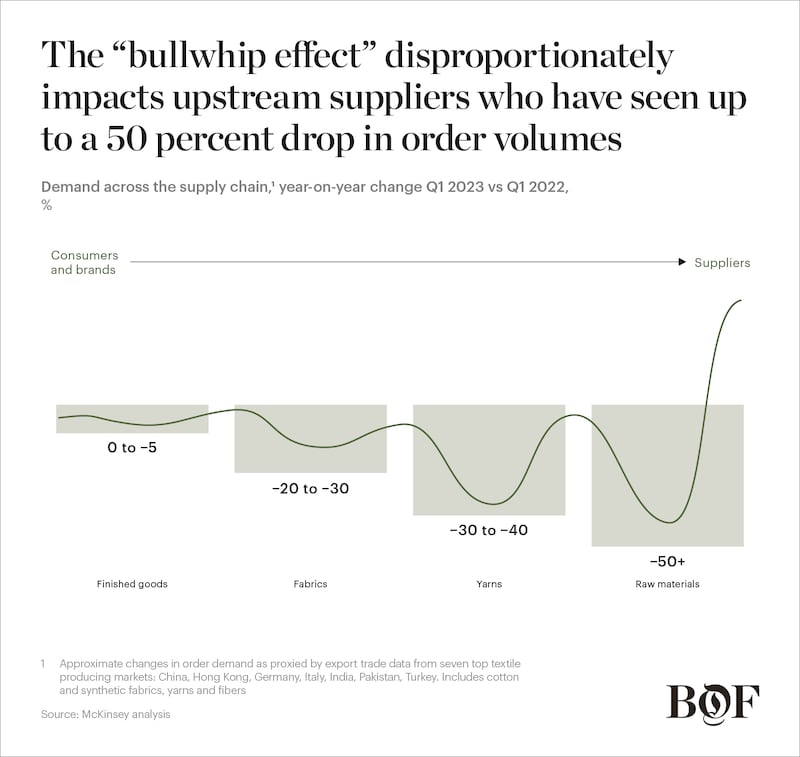

This turmoil is known as the “bullwhip effect,” a phenomenon where changes in consumer demand escalate across the value chain. In the case of fashion, changes in consumer demand are magnified at each step from retailers to garment manufacturers to yarn and raw material suppliers. In the face of falling demand, each part of the supply chain overcompensates by reducing forecasts, lowering production and decreasing order volumes — often driven by communication gaps and forecasting inaccuracies.

The bullwhip effect reached fashion in 2020 and 2021 as retailers contended with pandemic-related disruptions when products arrived late and overcompensated for inventory shortages by ordering too much stock. When post-pandemic inflationary pressures and economic uncertainty arose in the second half of 2022, making consumers more cautious than anticipated, retailers were left with billions of dollars in unsold goods. As a result, many orders for the upcoming 2023 season were reduced or cancelled.

The pullback has disproportionately impacted upstream suppliers. Across seven of the world’s biggest textile exporting countries, fabric exports dropped nearly 20 percent in the last quarter of 2022 compared to the year prior, followed by a 40 percent drop in yarn exports in the first quarter of 2023. Factories that were at full capacity in 2021 may have been operating at 30 percent to 40 percent below capacity in 2023, according to industry experts. It’s a similar story for textile machinery players. Swiss manufacturer Rieter reported a 63 percent year-on-year drop in orders in the first half of 2023, citing weakening demand for spinning technology.

ADVERTISEMENT

Smaller manufacturers with limited resources have been the most affected. The managing director of a manufacturer in Pakistan estimated that as much as 30 percent of the country’s textile factories have closed. In India, spinning mills have requested aid from the government, while many operate at a loss. Other manufacturing hotspots such as Sri Lanka and Vietnam have entirely shut operations in some factories.

The bullwhip effect has only made more urgent the humanitarian crisis occurring within textile-producing countries. For starters, a large share of textile and garment workers live on low wages and have little if any savings to fall back on. Today, the increased stress on factories could increase the risk of labour abuses, such as wage theft and union busting.

In China, the world’s largest textile producer, the number of worker strikes and protests rose in 2023. According to the China Labour Bulletin, more than 700 factory strikes in the first half of 2023 took place, compared to 800 in all of 2022. In Pakistan, loss of cotton crops from floods, shifts in production and lower exports contributed to over one million of its eight million textile workers losing jobs. Textile employment levels also fell by tens of thousands in key markets such as Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Cambodia and Turkey in 2023.

This supply-chain volatility is not expected to subside in the near term. A McKinsey survey of chief procurement officers (CPOs) in September 2023 found that 73 percent believe demand volatility will be one of the top challenges to affect supplier relationships over the next five years. However, the third quarter of 2024 is the earliest that textile factories might see some capacity improvement. But even then, the consequences of the bullwhip effect may continue to linger. Layoffs and delayed investments may mean the industry is insufficiently prepared to scale up capacity quickly.

Worker displacement and skills loss may create major challenges for the industry. In Vietnam, for example, competition for qualified labour is intensifying with other industries — suppliers to Apple, Lego and automotive players are among those expanding operations and attracting former textile workers in the country. Factories short on staff and dealing with hiring and training new employees could face longer production timelines.

Brands and retailers not prepared for these shifts could incur higher expenses to compensate for the potential delays. For example, they may need to pay for expedited shipping, overtime work or additional warehouse space. Those that try to rush production face other costs, such as increased quality issues that can damage a company’s reputation with consumers.

Many companies are rethinking their supply chains to de-risk manufacturing. According to McKinsey’s CPO survey, 54 percent of executives expect to increase reshoring or nearshoring in 2024. Others are thinking about rebalancing their sourcing footprint by sourcing from multiple countries. However, these approaches are not without challenges. Finding and contracting new suppliers, or partnering more closely with existing strategic ones, can be costly. Companies can also run into manufacturing limitations compared to traditional sourcing hubs or face new regulatory and compliance factors.

Another consequence of the slowdown is that suppliers have fallen behind in critical investments in new infrastructure for both speed and sustainability. More than 70 percent of fashion’s greenhouse gas emissions stem from upstream activities, such as producing and finishing textiles. Yet, textile players say costs are high for upgrading machinery or adopting greener practices. Without a steady stream of orders, they are postponing capital expenditure on such initiatives. Unifi, a US-based manufacturer of recycled and synthetic fibres, has delayed machinery replacements from 2024 to 2026 to offset slowing demand.

ADVERTISEMENT

With sustainability regulations coming into effect in the EU and elsewhere that mandate companies disclose environmental impacts in their supply chains, and the push from investors for companies to disclose data about scope three emissions (that is, indirect emissions), the risk may only increase for brands and retailers.

In the year ahead, brands might consider placing greater emphasis on making their supply chains more resilient to mitigate future risks. First and foremost, transparency and communication among all stakeholders in the supply chain will likely be paramount in facilitating better information-sharing and joint demand forecasting. According to McKinsey’s survey, 70 percent of chief procurement officers believe that improving demand transparency with suppliers through systems and processes is critical in navigating market turmoil.

Cultivating strategic partnerships with key suppliers could also be considered and could include longer term contracts with not only direct suppliers, but also tier two, tier three and tier four partners that are vital to a business. One potential benefit of such a long-term commitment is that it can provide a supplier with cash flow to invest in industrial and sustainability improvements at its facilities, according to Florian Heubrandner, executive vice president of global textiles at Lenzing, a wood-based cellulosic fibre manufacturer.

Brands should also continue to actively champion workers’ rights. This includes ensuring fair wages, job protection, safe working conditions and opportunities for professional development for factory workers. Beyond enabling two-way communication with suppliers about this, companies can take steps on their own. Adidas, among other companies, has established a worker hotline to enable workers to voice complaints that it can then work to resolve. Similar initiatives include PVH’s, which includes setting up representative workplace committees for all workers employed by key suppliers by 2025.

The upheavals of recent years have made clear that fashion companies and their suppliers not only depend on each other to succeed, but also endure challenges together. 2024 will likely provide further evidence as to why.

This article first appeared in The State of Fashion 2024, an in-depth report on the global fashion industry, co-published by BoF and McKinsey & Company.

The eighth annual State of Fashion report by The Business of Fashion and McKinsey & Company reveals an industry navigating deep uncertainty. Download the full report to understand the 10 themes that will define the industry and the opportunities for growth in the year ahead.

Adidas has mounted one of the more remarkable turnarounds in recent memory after facing a crisis two years ago from the end of its Yeezy business. BoF spoke to chief executive Bjørn Gulden and other members of Adidas’ leadership to unpack how a series of bold decisions on products like its Samba sneaker, a move to refocus the brand on athletes and internal shifts brought Adidas back from the brink.

In 2024, US shoppers spent more than $14 billion online during Amazon’s 48-hour Prime Day sale. Here, Front Row’s Alexandra Carmody shares how Deal Day strategies can drive lasting success beyond immediate sales spikes.

A slew of brands should report strong results even amid an unpredictable economy and slumping luxury sales.

The dream of creating an American answer to LVMH and Kering faced a major setback this week after a federal judge championed the Federal Trade Commission’s narrow definition of the sub-luxury handbag market.