Agenda-setting intelligence, analysis and advice for the global fashion community.

Agenda-setting intelligence, analysis and advice for the global fashion community.

When the Austin boutique ByGeorge stocked its first Stòffa collection in November, there was already a waitlist of customers eager to buy the menswear brand’s $600 wool trousers and $1,600 shirt jackets. Albert Mendez, the store’s buyer, said he rarely sees that level of anticipation, even for the latest Zegna or Thom Browne.

Stòffa, a 9-year-old New York-based label, has long had a devoted fan base of tastemakers, among them Nordstrom men’s fashion director Jian DeLeon and the restauranteur Mario Carbone. But it’s undeniable that momentum around the brand is picking up, propelled by a shift from logo-heavy streetwear to sleek, understated “stealth wealth”-inspired clothing. Stòffa has emerged as the lesser-priced (though certainly not cheap) alternative to The Row or Lemaire. It also offers custom clothing, again at a price point a step below luxury’s top tier.

“[Stòffa is] perfect for the moment,” said Chris Black, founder of the brand consulting agency Done to Death Projects. “If people are striving to dress [in a quiet luxury] way, then they’re … going to be seeking out new things, and that’s where Stòffa can take some market share.”

Founders Agyesh Madan and Nicholas Ragosta aren’t shy about their ambitions: they want to grow Stòffa from a niche label for in-the-know menswear aficiandos into a heritage brand like Loro Piana. They’re starting to put the pieces in place, rolling out new product lines and entering new distribution channels. In September, Stòffa introduced its first shoe collection, which has sold out twice since launch, the company said. In January, the brand will open its first store, a 2,000-square-foot outpost in New York’s SoHo neighbourhood that will include a private-selling salon for made-to-measure appointments and ready-made items like shoes and accessories.

ADVERTISEMENT

Madan and Ragosta are playing the long game, however: the co-founders haven’t raised venture capital (Stòffa has been profitable from the start), and say they’re prepared to spend the next 30 years to reach their goals, if that’s what it takes. For now, they’re focussed on doubling sales to $10 million by 2025.

“We’re not building a business first and using fashion as the vehicle to build that business,” Ragosta said. “Our passion and our drive was [always] to build a brand and a product and a team.”

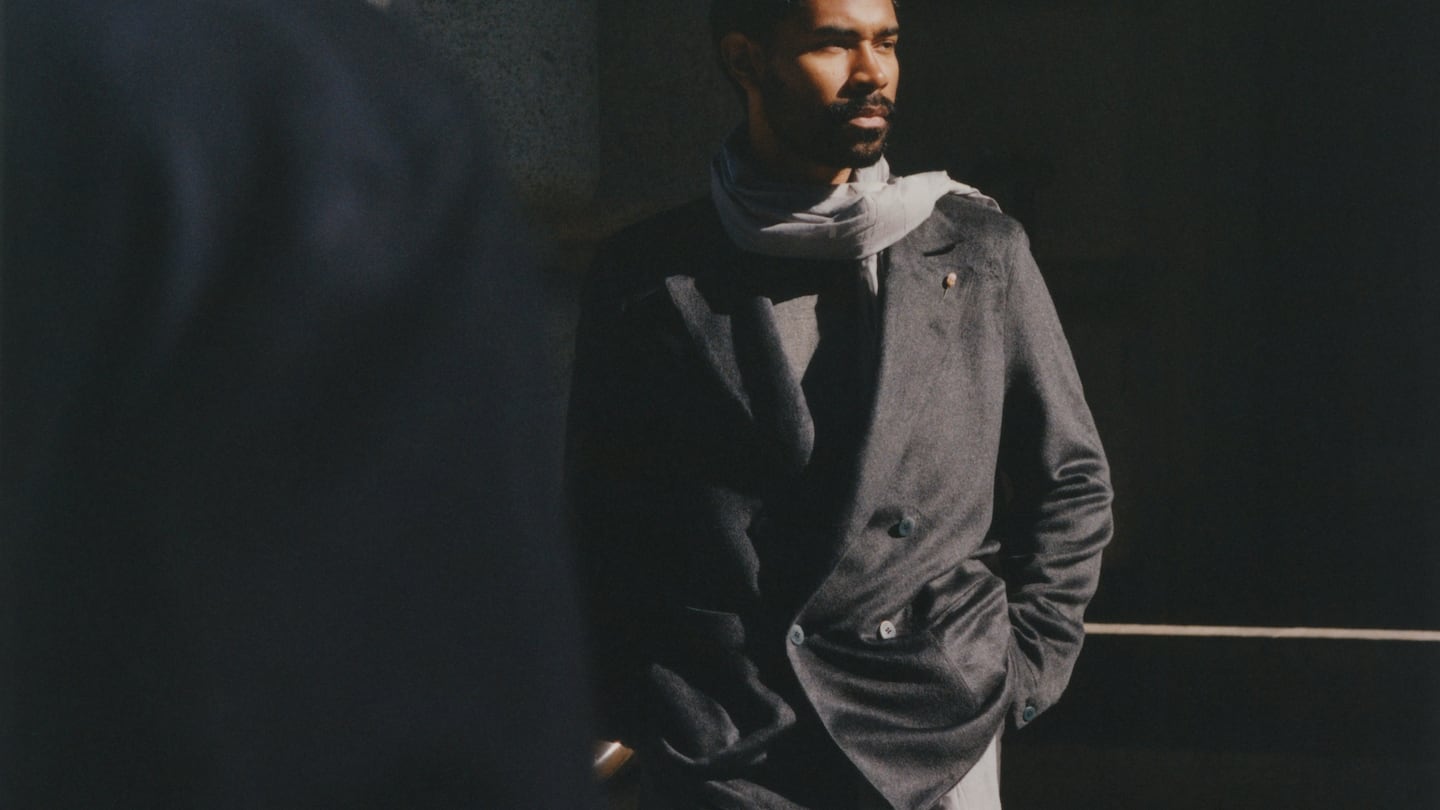

With Stòffa, Madan and Ragosta’s (who first met working at Italian suit maker Isaia) goal was to bring high quality materials and a made-to-measure service to a generation of more casually-dressed consumers. Think a double-breasted shirt jacket in silk or cashmere paired with single-pleat trousers in flannel worn under an overcoat in herringbone wool.

To meet customers in its early years, Stòffa held trunk shows once a month in cities like New York and London, where prospective clients could view the brand’s collections and get measured for custom-made garments. Once their measurements were in Stòffa’s database, customers could then place subsequent orders online.

In 2018, the brand opened its first showroom, in New York, as a permanent location to host that experience for customers. Today, the made-to-measure business in Stòffa’s showroom accounts for 60 percent of its DTC sales. In online orders, 30 percent are returning customers buying more custom pieces.

Stòffa’s growth has been powered by strong customer retention, which the brand attributes to its focus on made-to-measure and marketing strategy. Over 40 percent of the past year’s sales are from repeat customers.

In the past seven years, Stòffa has spent just $15,000 on paid social media ads, in contrast to the millions many digitally-native brands shell out annually. Instead, it focuses on creating digital lookbooks for each product drop that are sent to prospective and new customers through the company’s email newsletter — efforts it spends less than 20 percent of annual revenue on.

“We need really qualified leads because our clients shop a lot and stay with us for a long time,” Madan said. “You booked an appointment, you came up to the second floor of [our showroom], you’re qualified already … you already are committed in a way that it’s not just clicking through [an ad] to get there.”

ADVERTISEMENT

Holding down marketing costs has helped Stòffa to generate annual profit margins of 7 to 20 percent on the basis of earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortisation.

Stòffa’s reticence to chase short-term ubiquity informs its wholesale strategy. The company partners with only a handful of third-party retailers to sell ready-made inventory, including boutiques like ByGeorge and CHCM in New York, and e-tailer Mr Porter.

But Stòffa’s forthcoming flagship store will broaden its appeal to a wider pool of shoppers, the co-founders say. The space, for example, will allow the brand to host more of the events it currently holds in its showroom for product launches and crossover collaborations with artists and sommeliers, where existing clients will be able to bring as many of their like-minded friends as they want.

Madan and Ragosta believe that taking a more measured approach to Stòffa’s expansion will help them reach their lofty aspirations: Earning the heritage status typically reserved for decades-old labels like Loro Piana and Zegna.

It’ll be a challenge without the 100-year history and luxury conglomerate-backing.

“That’s impossible to replicate,” Done to Death Projects’ Black said. “But Stòffa can break through and be a go to for what they’re doing.”

For starters, its forthcoming flagship store in SoHo lays the path to more store openings overseas — the brand is currently eyeing spaces in London, where it still holds bi-annual trunk shows. Down the line, Stòffa’s retail expansion may include working with distribution partners who can open stores in Asia and elsewhere in Europe.

Stòffa is taking a similarly careful approach to the product. Since trousers are one of its best sellers, Stóffa is eploring expanding into denim, and because it already has its own proprietary fabrics, it sees a potential opportunity in small leather goods, often a luxury cash cow. In the coming years, Stòffa may sell its fabrics to other brands, as Loro Piana and Zegna have done, and is open to partnering with a conglomerate that could also provide capital and expand Stòffa’s supply chain.

“We want to be able to leave a bigger stamp or leave a bigger legacy that can be taken forward by other people in the future,” Madan said.

Established luxury brands, emerging designers and buzzy technical players alike mixed relaxed suiting with sportswear at the influential Pitti Uomo trade show.

A crop of fast-growing custom brands is serving the modern menswear consumer who wants not only custom suits but custom casualwear too.

Luxury brands may have pivoted away from sneakers, puffer jackets and hoodies, but new brands like Corteiz and Free The Youth are making the case for street culture’s enduring relevance in fashion.

Malique Morris is Direct-to-Consumer Correspondent at The Business of Fashion. He is based in New York and covers digital-native brands and shifts in the online shopping industry.

Senior correspondent Sheena Butler-Young and executive editor Brian Baskin are joined by e-commerce correspondent Malique Morris to explore how brands are offering affordable alternatives to luxury goods, and reshaping consumer expectations in the process.

With rising competition to acquire and retain customers online, digitally native start-ups are determining how to strike a balance between developing their own e-commerce features in-house and partnering with external software providers.

Start-ups like Quince and Italic that sell affordable basics made in the same factories as high-end brands are generating massive growth in appealing directly to middle-class shoppers who don’t want to resort to Shein hauls.

The upside for online sales may be lower than many retailers anticipated. Physical stores and social commerce could make up the gap.