Agenda-setting intelligence, analysis and advice for the global fashion community.

Agenda-setting intelligence, analysis and advice for the global fashion community.

This article is part of BoF's special edition, Can Fashion Clean Up Its Act? Click here to learn more.

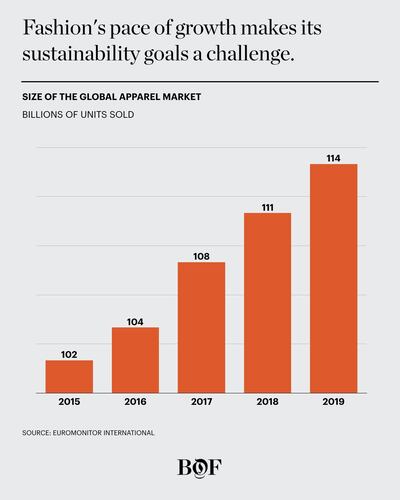

LONDON, United Kingdom — Last year, 114 billion items of clothing were sold globally, the equivalent of nearly 15 new garments for every person on the planet.

Fashion brands have made an enormous amount of money off the "more is more" trend, whether it's Zara owner Inditex more than doubling sales of its fast fashion over the course of the decade or luxury goods giant LVMH ascending to become the second-most valuable company in Europe, with a market capitalisation topping €200 billion ($220 billion).

But the singular focus on growth is increasingly at odds with the industry's public commitments to tackle its role in climate change. In the last 12 months alone, companies including fast-fashion giant Zara and Tommy-Hilfiger-owner PVH Corp have laid out new targets. Roughly a third of the industry signed up to a new sustainable fashion pact, which brought on-board luxury players, like Prada, Hermès and Chanel, that have historically remained aloof from broad initiatives.

ADVERTISEMENT

There’s just one problem: many experts agree that it will be difficult, if not impossible, to meet those goals within the framework of fashion’s growth-obsessed business model.

“There’s going to be a crash landing when we reach the point where they can’t reach their environmental targets and make money,” said Linda Greer, a consultant and senior global fellow at the Institute of Public and Environmental Affairs. “It’s the elephant in the room.”

To date, big brands have largely addressed climate goals by investing in material innovations and technologies that make manufacturing more efficient. But that's not enough; fashion production is on track to rise 81 percent by 2030, and innovations aren't progressing fast enough to offset the negative environmental impact, according to Copenhagen-based sustainable fashion forum and advocacy group the Global Fashion Agenda.

Even some of the industry's most vocal advocates on climate aren't facing up to this issue. Luxury conglomerate Kering, which spearheaded last year's fashion pact, has set an ambitious target to reduce its overall environmental impact 40 percent by 2025, but its progress has been limited by its success. In 2018, the company succeeded in reducing its footprint by 12 percent as a proportion of revenue compared to a year earlier, but on an absolute basis that was fully offset by the company's rapid growth.

Kering's head of sustainability Marie-Claire Daveu said the company is focused on investments, innovations and efficiencies that will materially reduce its impact. Only focusing on reducing growth won't transform the industry, she argued.

There's going to be a crash landing when we reach the point where they can't reach their environmental targets and make money.

“You can’t pit purpose against profit,” Daveu said. “You can be efficient and sustainable and make profit… we never said we will stop producing.” On Monday, the brand was recognised for its efforts to tackle global warming when it was named on nonprofit CDP's A list of companies at the forefront of efforts to tackle the climate crisis.

But the fact remains that in the end, a new shirt, bag or pair of shoes sold will require more cotton, wool, leather or plastic.

“Overproduction is the thing so few people want to engage with,” said Rebecca Robins, global chief learning and culture officer at Interbrand. “At the end of the day, the core premise of any retailer is that there has to be a transaction.”

ADVERTISEMENT

The End of Fashion as We Know It

The conversation is slowly beginning to gain high-level traction within the industry. It will be front and centre at the World Economic Forum in Davos on Tuesday, where the GFA is leading a roundtable on redesigning growth. The Copenhagen-based advocacy group is launching an update to its CEO Agenda, a set of priorities for executives focused on reducing the industry's impact near-term. But looking forward, it is working to get fashion to come to terms with its growth conundrum.

"We simply need to redesign the way we think and talk about value and growth and prosperity," said GFA Chief Executive Eva Kruse. "It's a much bigger concept than just implementing practises that minimise and optimise; it challenges 100 years of thinking about the need to grow and become more wealthy."

Facing multiple external pressures, some brands are beginning to quietly make changes to the way they approach their business, trying to incorporate this new way of thinking.

“We foresee and we support the end of fashion as we know it today,” Esprit wrote in its sustainability report published at the end of last year. “The fashion system of recent years is now obsolete, and in its place we want to foster a new kind of a system, where sustainability and circularity become the new normal.”

In the midst of a broader turnaround effort, the company slashed the number of products it offers by 23 percent last year. It's poured €30 million ($33 million) into improving the quality of the products that are still hitting the shelves. The strategic shift is not just about sustainability. Esprit has been struggling and needed to sharpen its brand identity and improve its product offering, but it is nonetheless finding value in reduced volumes.

We simply need to redesign the way we think and talk about value and growth and prosperity.

“It hurts your bottom line, but we’re looking longer-term,” Chief Executive Anders Kristiansen said. “Our volumes will go down, and over time our prices will go slightly up; if we create a much better product, not just sustainably, but a much better quality product, we think we can, and should, charge more.”

Elsewhere, a growing number of fashion companies, including Patagonia, Allbirds and Eileen Fisher, have become B Corporations, which means they're certified to have considered the impact of their decisions not just on the bottom line, but also on people, society and the planet. In theory, it provides a different framework to measure business success than the simple metrics of growth and profit.

ADVERTISEMENT

Even the financial industry that underpins companies' ravenous growth appetite is beginning to shift its language. Last week, the world's biggest fund manager, Blackrock, said climate change "has become a defining factor in companies' long-term prospects," predicting "a fundamental reshaping of finance."

Searching for an Endgame

One challenge for fashion is there’s no clear endgame. While the power industry can look to shift to renewable energy, and the car industry is gearing up for an electric revolution, fashion is in a limbo. The idea of a fully circular business model, where clothes can be recycled again and again in a closed loop without any need for virgin materials is not yet close to reality.

Among other things, companies are looking at new business models like rental, resale and repair to maximise the revenue stream generated by a single item. Last year, H&M group took a majority stake in re-commerce platform Sellpy and it's testing out rental and repair services. The second hand clothes market is expected to nearly double in size by 2023, according to analytics firm GlobalData, while re-commerce platform The RealReal's IPO last year valued the company at around $1.6 billion.

It hurts your bottom line, but we're looking longer-term.

“There’s a lot of transformation the industry is undergoing right now, one side is to reduce the footprint of products further, and the other side is how we can create revenue from not only selling new products,” said Hendrik Alpen, engagement sustainability manager at H&M group. “That’s a really strong business case: how many times can we make a revenue stream out of one product.”

But for these new business models to have an impact, virgin production levels need to come down. While that's not happening, they run the risk of simply enabling and encouraging more consumption. In the meantime, the risks are growing. Fashion, with its reliance on raw materials, is likely to feel the financial impact sooner than other industries.

“It’s about future-proofing their business models,” said GFA’s Kruse. “Those ready to adapt and rethink the models will be the ones that will survive best.”

And yet there remains a disconnect between the activists and experts driving for change and the day-to-day reality of business. Earlier this month, Kering-owned Balenciaga came under fire for plans to sell koala-print hoodies and T-shirts in order to raise money to help with wildfires that have raged across Australia for months. The move sparked outrage on parts of social media, where critics panned the company for trying to push new and wasteful products when the disaster is linked to climate change. On the other hand, the drop was also largely embraced in the mainstream.

“You’re adding to the problem,” said Dio Kurazawa, founder of sustainable supply chain consultancy The Bear Scouts, before adding, “they will probably sell out.”

Related Articles:

[ How Can New Technologies Help Make Fashion More SustainableOpens in new window ]

[ In Search of a Business Case for SustainabilityOpens in new window ]

[ What’s Stopping the Fashion Industry from Agreeing on Climate Action?Opens in new window ]

As the EU seeks to crack down on a growing glut of clothing waste, the rise of low-value ultra-fast-fashion, along with increased competition and geopolitical disruption, are putting pressure on the economics of collecting, sorting and recycling used textiles.

After a pandemic contraction — and with a new CEO on board — the godmother of mindful consumption is gearing up to grow (mindfully).

Cheap and versatile polyester has underpinned both the fashion industry’s growth and its worsening environmental footprint. Efforts to switch to recycled fibre are stalled, new data show.

This week, New York hosted the “unofficial climate summit of the year.” But the effort to move the needle on climate action feels as gridlocked as the traffic in midtown Manhattan.